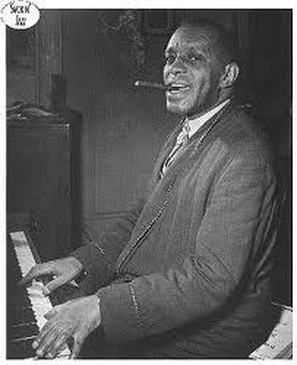

Willie “The Lion” Smith: Born 1897; Died 1973 Musical Selection: “Crazy Blues” Smith was born with the considerable name of William Henry Berthol Bonaparte Bertholoff, coming from a mixed-race marriage, Black and Jewish, but with his father dying when Willie was just four, and his mother’s subsequent marriage, the young Bertholoff later took on his stepfather’s surname. Smith was born in Goshen, New York, but grew up in Newark, New Jersey, learning piano from his mother, who was a church player. Smith’s main musical education was, by his own account, somewhat haphazard, but he was a quick learner and by 1914 he’d made his professional debut. Smith was soon plunged into the hectic and informal music world of Harlem, learning the emergent ragtime strain peculiar to the Eastern Seaboard, which, combined with elements of the gospel piano style and the urge to improvise on dance forms, would soon evolve into what would later be termed “stride.” He also learned the essential style accessories for the stride pianist, from his hat and cane (often accompanied by the biggest cigar available) to the braggadocio speech styles and flamboyant keyboard techniques, all of which would also be developed into a personal identifying trait by pianists such as Luckey Roberts, James P. Johnson, and Fats Waller, and which were very evident in the attitude evinced by New Orleans keyboard man Jelly Roll Morton, whom Smith often saw playing in New York prior to World War I. In late 1916 Smith volunteered for active service in WWI, after a training period being shipped off to the Western Front in summer 1917. Trained in artillery, he proved highly capable and was promoted to the rank of sergeant; he also claimed to have picked up his nickname, “The Lion,” there, bestowed on him by an officer inspecting the front, who was told of his expertise with large-bore artillery and his unusual stamina. Smith made sure the nickname struck. Having left the military in 1919, Smith returned to his old ways in Harlem, fast becoming one of the standouts in the emergent stride school, striking up friendships during the 1920s with the likes of Fats Waller and, especially, Duke Ellington. Smith began appearing on records (he was the accompanist to Mamie Smith on her trend-setting “Crazy Blues” of 1920) and ran his own small group at Harlem’s Leroy’s as well as, later one, the Onyx Club, Pod’s, and, finally, Jerry’s. Smith was a legend among fellow professionals but largely unknown to the general public until he began recording a series of piano solos for Decca in 1935. The striking individualism of these brought him a ready audience on both sides of the Atlantic, which he began to exploit after World War II through regular tours, even reaching North Africa in 1949-50. After that Smith was a regular part of the jazz and entertainment scene, his compelling character and stylized mode of dress making him instantly recognizable. During the 1960s he began to feel the need to document his life and the music he had grown up with: in 1965 he produced (with George hoefer) his autobiography, Music On My Mind, while for RCA in 1969 he recorded The Memoirs of Willie “The Lion” Smith, a two-disc LP set of his talking and playing. Smith died in 1973 an honored and feted man in the US and Europe.

0 Comments

James P. Johnson: Born 1894; Died 1955. Musical Selection: “Yamacraw”, “Symphony Harlem”. Pianist-composer Johnson was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey, learning music from his mother. He moved with his family to New York in 1908, making a regular living at music before the end of the decade. Johnson eagerly took in all the music then thriving in New York, including ragtime, classical, and blues, and was serving up his version of all this to clients at various mid-town New York dives in the years prior to World War I, cutting his first cylinder rolls in 1916. Equally adept at theater music, Johnson traveled after the war to England with the show, Plantation Days, then on his return began to establish a reputation as a first-rate composer of show tunes, completing the score for the hit show Runnin’ Wild in 1923. By this time his driving piano style had matured into the stride left-hand figures for which he and other New York pianists of this time were to become world famous. Johnson, however, was more than just a pianist and songsmith, for during the 1920s and 1930s he consistently completed larger-scale, through-composed works, such as Yamacraw and Symphony Harlem, many of which were premiered in New York but most of which failed to find an audience: at this time, a black writing serious music simply had no niche to aim for. Undeterred, Johnson continued to compose, writing operatic works as well as, in 1938, completing a symphonic treatment of, “St Louis Blues.” For the rest of his career Johnson continued to write ambitious works and to play with a range of groups in and around New York, establishing himself undeniably as a significant figure in the jazz scene; he also stayed involved in revues and musicals, writing the music for 1949’s Sugar Hill; unfortunately, a stroke in 1951 rendered him incapable of actively pursuing his career any further. He died four years later.  Jelly Roll Morton: Born 1890; Died 1941. Musical Selection: “King Porter”, “Jungle Blues”, “Black Bottom Stomp” For many years there was confusion over Morton’s date of birth: 1889 on his death certificate while other commentators pushed for 1885. The precise facts were established by Lawrence Gushee. He also found that Morton, born Ferdinand LaMenthe (the family name was LaMothe and he was baptized Lemott) in New Orleans, took the name Morton from a stepfather (who’s name was actually Mouton!) Morton started out on guitar as a boy before switching to piano in early adolescence. He claims to have been playing Storyville bordellos in 1902, though a date closer to the middle of the decade is more realistic; here he met and learned much from pianist Tony Jackson before moving on to other parts of Louisiana and Mississippi. Between 1906 and 1908 he traveled from Florida to California as well as Chicago, St Louis, and Houston, making money as a hustler, pool shark, part-time pimp, and all-round con man as well as learning much from the pianists he encountered, including the legendary “Jack The Bear.” In 1909 he worked in a Memphis theater, then joined a vaudeville team eventually making it to New York. Morton spent time in Chicago, running his own band in 1914-15, then pushed on to LA, where he met Anita Gonzales, later his wife, and more than once made it as far as Mexico. In 1923 Morton moved to Chicago, attracted by a booming music business there and the chance of recordings and piano rolls. That year he debuted on both recording media, also finding work with the Melrose publishing company and running his sometime band, the Rid Hot Peppers. In 1926 Morton began making the series of 78s for the Victor Company, which were to seal his jazz reputation. These were with his studio band, the sometimes septet/octet, the Red Hot Peppers, a band often featuring clarinetist Omer Simeon, trumpeter George Mitchell and trombonist Kid Ory. The style was New Orleans, but very much Morton’s own idea of New Orleans: in fact, his arrangements, allied to his humor and compositions, made for a vivid portrayal of the hybrid form of jazz. Pieces like “The Pearls,” “King Porter,” “Jungle Blues,” “Black Bottom Stomp,” “Dead Man Blues,” “Sidewalk Blues,” and many more all testify to his unique abilities. Compared with contemporaneous dance arrangements and tunes in 1926-28, Morton was streets ahead. Unfortunately, he alienated many people who could have helped, including the MCA booking agency. A Move to New York in 1928 presaged his eclipse. Morton wanted no part of the emerging big-band movement. In 1930 his Victor contract was not renewed. Down on his luck he made one Wingy Manone session in 1934 before moving to Washington, DC, once more leaving music for a period. Working as a pianist in a lowlife Washington club, Morton was approached by folklorist Alan Lomax to make a series of recordings for the Library of Congress in late summer 1938. The resulting records are one of the greatest first-hand archives of New Orleans testimony in existence. In between sessions, however, he was stabbed in a brawl at his club, triggering a round of ill health. A move back to New York in 1938 and radio appearances in the Big Apple let to Morton recording with Sidney Bechet and Albert Nichoas, making a fine session for Bluebird. Morton mad further records for General, piano solos, and group recordings, which show him to be in complete command of his abilities. If he had lived, he would undoubtedly have become a focal point for the 1940s revivalist. His deteriorating health was exacerbated by a cross-country winter drive 1940-41, and by the summer of 1941 Morton was dead. |

Jazz LegendsA blog on the great legends in Jazz. Information via "The Encyclopedia of Jazz and Blues". Archives

December 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed